Featuring Professor Eric Hupe, Art

Works of art ask us to engage, and include us in the scene. It’s not just an old relic of the past but something that is visceral. It is visually participatory… Virtual reality allows for that participation. With virtual reality, I want students to be dropped into a place, engage with the art and think to themselves, “how do I wrestle with this?”

– Professor Eric Hupe, Art

Professor Eric Hupe, new to Lafayette College, sits in his office surrounded by postcards of art works collected at various museums. These low tech pieces of memorabilia call back to a tradition of many art scholars who collected postcards because it was the only way to bring a work of art home. In contrast to the postcards, Professor Hupe also houses Google Cardboards, Oculus Gos and Oculus Quests, virtual reality (VR) systems that give viewers a 360-degree experience of art. Supported by the Teaching with Technology grant, the VR Professor Hupe uses in his class allows him to change the way Art History can be taught and consumed,

The standard form for showing different artworks is PowerPoint. Art history is always a slog through hundreds of slides and hundreds of images which does not necessarily invite students to think critically about how objects are made, how they are a part of a larger ensemble, or the scale of the art. And art is always about scale. Art cannot be divorced from its setting. We lose something in that transition. Works of art ask us to engage and include us in the scene. It’s not just an old relic of the past but something that is visceral. It is visually participatory. It was believed during the Renaissance period that vision and the consumption of art could alter someone’s body and I believe that art still has the power to do that for us even though our sense of vision and what it does has changed.

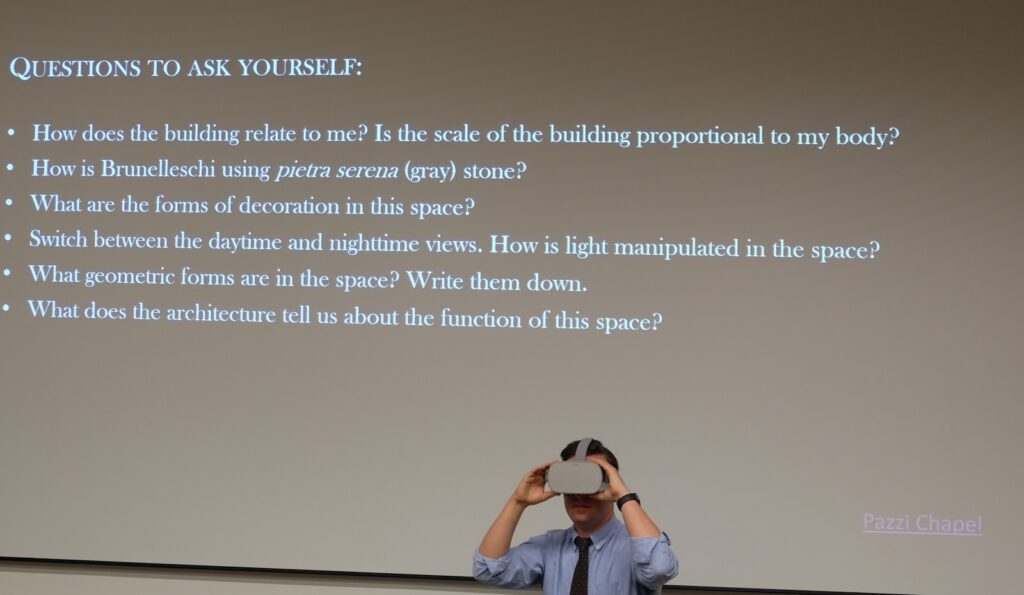

Professor Eric Hupe stands in front of his class and takes students on a virtual reality tour of the Pazzi Chapel

Professor Eric Hupe stands in front of his class and takes students on a virtual reality tour of the Pazzi Chapel

Walking into Professor Hupe’s class you can see students engaging with VR and asking each other pointed questions about the works they are exploring. There is a general sense of wonder and amusement that is fostered through this experience and that is paired with the learning objectives of the class,

There is an initial surprise and excitement around VR, but I’m very cautious about using this stuff, I don’t want it to become hokey. I want to make sure that there is actual learning happening. We always talk about these really boring, important, but kind of boring concepts in art like axiality – how buildings are arranged to be along an axial path that is often a processional path. This is really important for understanding works of architecture. Instead of just lecturing if I can put a student there on an axial line and say, “look this way, look that way and what do you notice?” They learn the concept themselves. They often say, “Wow, everything is perfectly in order and in line with each other and there is this processional way.” And then I can say, “That’s axiality, why don’t you walk the line and tell me what you see?” That’s a much better way of explaining this architectural concept and the importance of it as opposed to showing a diagram which is what you have to do without the VR. I’m trying to find more inventive ways to continue using VR to describe some of these basic disciplinary standards.

VR also affords students access to sites that they may not have the chance to experience themselves,

I only started traveling much later in life. I didn’t have the opportunity to go to Europe at an early age and see all these things. VR is democratic in the sense that it can transport you without having to travel. Something like the Google Cardboard is relatively inexpensive. You don’t have to have a six hundred dollar unit to experience European art in its setting. Also, there is limited access to some of these sites. I would love to take my students to Europe all the time but VR at least gives us an approximate feel for the time we are here in the states.

The intimacy that is afforded to VR users is also apparent when students get to enter spaces like the Gubbio Studiolo, a private study created in the 15th century and completely decorated with images made out of inlaid wood.

The Gubbio Studiolo

From: https://www.metmuseum.org/en/art/collection/search/198556

Students are overwhelmed by the amount of decoration that is there and that intimacy is important to understanding the function of the room and students – it helps with that level of observation. When you see photographs of the room it is a fish eye view where you get these large panoramic views of it. But it’s a tiny, tiny space. All the allusions in the woodwork are to the scale of you standing in the environment…and art is always about scale. Something like the Mona Lisa is conflated to be this huge masterpiece and then when people actually see it they realize it is relatively tiny. And that is a part of what the Mona Lisa was – it was a portrait of someone, it was meant to be transportable and easy to move around. It’s not shocking to me but I want students to get a sense of that scale and the ways in which we as observers move through and interact with art.

This desire for students to have authentic interaction with art through VR is also reflected in Professor Hupe’s interaction with students more generally on campus. He chose to work at Lafayette because of its focus on teaching and learning and the ability to have real and authentic student connections. Lafayette is also a place where Professor Hupe has found other VR enthusiasts and has recently co-created a Virtual and Augmented Reality Community of Practice. As Professor Hupe continues to use VR and test the boundaries of time and space, students at Lafayette College will surely benefit from being able to say, “I’ve been there, that work of art spoke to me and I spoke back.”

Learn more about Professor Hupe’s VR implementation here

If you are interested in joining the Use of Virtual and Augmented Reality in Pedagogy and Research Community of Practice, please reach out to Professor Eric Hupe (hupee@lafayette.edu) for more information.